Two daughters and sons-in-law

At the height of their popularity two of South Asia’s greatest politicians — and bitter rivals — were struggling with an identical personal trauma, their Parsi sons-in-law. One a Kashmiri Brahmin, the other a Khoja Muslim, Nehru, and Jinnah were household names in the 1930-40s. They had a daughter each to dote on but their sons-in-law were to give them grief. Both the leaders were secular but, on hindsight, betrayed a lurking conservatism that showed up when it came to their daughters’ cross-cultural suitors.

The backdrop to this narrow-mindedness was similarly stark. Nehru despite his eclectic worldview agreed with a prevailing narrative that a Hindu-majority India would not accept a Muslim prime minister. The dapper Jinnah with his liberal persona believed that bereft of Hindu hegemony and left to themselves, Indian Muslims could set up their own secular state, at par with stringent standards of secular democracy both leaders were exposed to as students in England. Both had miscalculated as they failed to factor the power of cultural and religious atavism that would stalk and waylay their poorly grounded quest. Their Parsi sons-in-law should have melded well with their liberal grooming, but instead, brought them little relief.

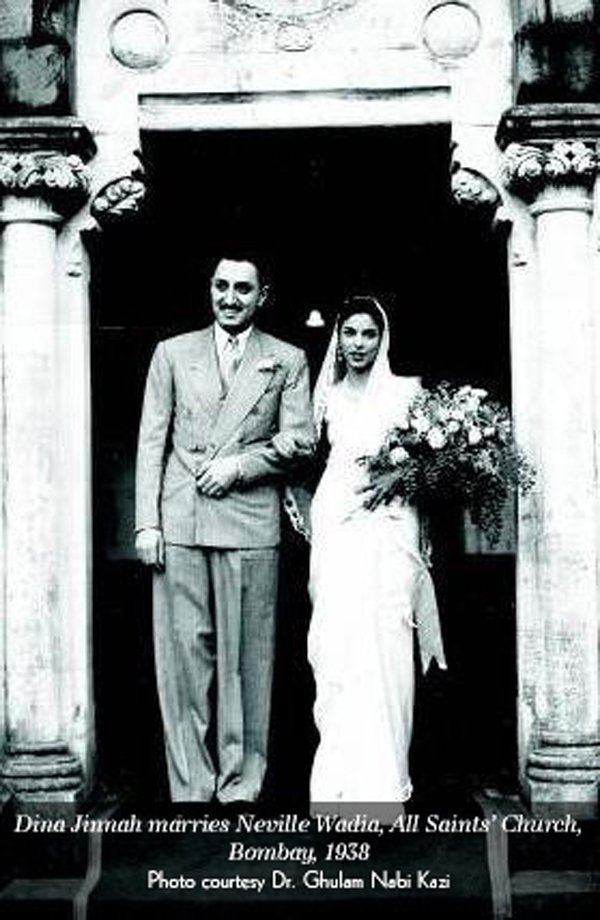

Jinnah’s only child Dina married Neville Wadia in 1938. Indira, Nehru’s only child, married Feroze Gandhi in 1942. Dina died in New York on Nov 2. She was 98, two years younger to Indira Gandhi, who was 67 when she was assassinated in 1984.

They both had love marriages against their parents’ wishes and both fell out with their husbands — after five years in Dina’s case, and a few more in Indira’s. Each had two children. Dina and Neville had a son and a daughter — Nusli and Diana — from their marriage in 1938. The couple split in 1943 though a formal divorce never took place. Indira and Feroze Gandhi had two boys — Rajiv and Sanjay from their marriage in1942. Their marital discord became a factor in their politics until 1960 when Feroze passed away at 48.

According to Swedish journalist Bertil Falk, who discussed his new book on Feroze Gandhi in Delhi recently, Nehru’s son-in-law was a Democrat of rare mettle. Possessing charm, intelligence, and tenacity, Feroze had a lovely sense of humour as well as a commitment to truth and improving a lot of the poor. He had an early hint of Indira’s wilful leadership style and warned her not to succumb to the temptation of authoritarianism. “Feroze and Indira fought hard when Nehru persuaded by Indira sacked the communist government of Kerala in 1959,” Falk recalls. He says the subject came up at breakfast in Teen Murti Bhavan, the prime minister’s residence. Feroze, then Congress MP from Rae Bareli, apparently told Indira: “It is not just right. You are bullying people. You are a fascist.”

Nehru looked distressed, Falk writes, but an angry Indira retorted: “You are calling me a fascist? I can’t take that.” Falk says he heard the account from Nikhil Chakravarty, a senior journalist and a friend of Feroze.

“Feroze told Nikhil he had protested about Kerala to Indira Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru and said that fascism will come to Kerala. Indira flared up and said, ‘You mean I am a fascist’ and stormed out of the room,” Falk writes. Indira viewed Nehru as weak and indecisive, says Falk.

“He [Nehru] has given a very good lead from the beginning but he is incapable of dictatorship or rough-shedding over the views of his senior colleagues,” Indira had written to her American friend Dorothy Norman.

Following the breakfast table stand-off, Feroze spoke at a meeting of Congress MPs in parliament, questioning the Indira-inspired move for courting the church, the (Indian) Muslim League and the Nair Service Society to thwart the communists.

“Where is the Congress? Where are the principles of the Congress? Are we going to be dictated [to] by a caste monster we have produced?” Falk quotes Feroze as saying.

When Dina married Neville, Jinnah was furious despite having himself married a Parsi (who converted to Islam).

In her book, Mr and Mrs Jinnah: the Marriage that Shook India, author Sheela Reddy says that Jinnah saw Dina’s marriage to Neville as a serious political embarrassment.

“He tried to dissuade her [Dina] but finding her adamant, Jinnah threatened to disown her. Instead of relenting, she moved into her grandmother’s home, determined to go ahead with the marriage,” Reddy writes. She quotes Urdu writer Saadat Hasan Manto to state that Jinnah took Dina’s defiance badly. “For two weeks, he would not receive visitors. He would just go on smoking his cigars and pacing up and down in his room. He must have walked hundreds of miles in those two weeks,” Manto wrote.

Dina and Neville were said to have separated in 1943, but a formal divorce never took place. When Jinnah was rumored to be considering selling his Bombay home in 1941, Dina broke her long silence to pen a letter to ‘My darling Papa’.

Dated April 28, 1941, the letter is reproduced in Reddy’s book. It reads: “First of all I must congratulate you — on having got Pakistan, that is to say, the principle has been accepted. I am so proud and happy for you — how hard you have worked for it.”

Dina then comes to the subject of her primary interest. “I hear you have sold ‘South Court’ to Dalmia for 20 lakhs. It’s a very good price and you must be very pleased,” she writes. “If you have sold [it], I wanted to make one suggestion of you — if you are not moving your books, could I please have a few of Ruttie’s old poetry books — Byron, Shelley and a few others and the Oscar Wilde series?”

Jinnah’s reply was to summarily dismiss the purported house sale as a “wild rumor”.

Jawed Naqvi. Published in Dawn, November 7th, 2017